EXHIBITION MEDALS & AWARDS

(Page updated September 2020)

ACTIONS – ALIASES - ANCESTORS - ARCHIVES - AWARDS - BLOG –

DATEMARKS – DEMOS – DIAGRAMS – DONATIONS – DRY HEAT DAMAGE –

EDWARDIAN - EXHIBITION – FALSENESS - GENEALOGY – GEORGIAN – GRAND –

HEALTH – INVENTOR - KEYS – MEDALS - MEMORIES - NAMES – NUMBERS –

OCTAVES - QUERPIANOS - REPERTOIRE – SQUARES – STENCILS – TUNING –

UPRIGHT - VICTORIAN – WRESTPIN TORQUE

At a time in history when shopping malls and huge superstores did not exist, the international exhibitions were very impressive to people who had never seen anything on that scale. We receive a great many emails (as well as enquiries on the Piano History Forum) from people who are puzzled by the pictures of medals shown on their pianofortes, some of which have realistic miniature reproductions of one side of a medal, flat on the back so that they can be glued onto the piano. What they show us, mainly, is that the piano was made after the last exhibition that is listed on the piano. This information is often shown on hundreds or thousands of the pianos produced by that maker after the event, and it is only on very rare occasions that we find that the piano is the very instrument that was actually exhibited. Another form of confusion occurs when the piano is marked with the year the firm was established (German “gegrundet”) and it is for this reason that, for example, some people think Werner’s pianos were made in 1845, and choose to ignore the later years marked on his various medals.

As early as 1819, Erard received a medal at the Paris Exposition for his pianos, and many other pianofortes were awarded prize medals and awards at later exhibitions: these became important to the makers, but also to us looking back to learn more from a piano. The makers liked to show them off in the form of transfers or labels stuck inside, or in more obvious positions on the front. The medals are usually dated, and people often run away with the idea that this is the date of the piano, but the medals can only tell you that the piano was made in or after the latest year you can see.

For example, no reliable dates of Hagspiel serial numbers are available, but the dates of medals shown on the piano may help. These include 1873, 1875, 1876, 1880, 1884, 1893 and 1897. If a Hagspiel piano shows the 1880 medal, but not the later ones, we can assume that the piano was made after the 1880 exhibition, but probably not as late as 1884. Sometimes, the medals reveal that published dates of serial numbers are incorrect, as in a Nelson piano supposedly made in 1907, although it mentions a 1909 medal. Makers usually showed both sides of a medal, with the result that they looked like twice as many.

It’s important to mention that the labels showing the exhibition medals are sometimes made of paper, and may not survive, so the absence of medals is not reliable proof that the piano was made before an exhibition. An instrument that appears to have been made by Ecke around 1890 does not show any sign of the medals he received in 1880 or 1881.

![]()

The pictures above perhaps give some idea how important it was for German makers to try to include medals on their nameplates, or even two sides of just one medal, but this did not only apply to German makers, or to pianos. If they didn’t have any medals, they sometimes designed their logo to look like one, as Laurinat and Grossmann did. Richard Lipp received lots of medals, but he was also on some of the judging panels for the exhibitions, as was Anton Bord, who boasted the fact on his pianos.

What is clear is that some claims are misleading, and there are anomalies in the descriptions of medals and awards, often involving several different makers claiming the “Grand Prix” or "THE Gold Medal" or "Highest Award" at the same exhibition. The word "highest" may seem to imply that it is higher than anyone else's, but this is not always the case, and the highest award is usually a gold medal, sometimes awarded to a number of makers. Some names claiming medals are not even listed in the exhibition catalogues, and their claims seem dishonest.

In this Allison example, the latest date shown is 1885, and this tells us that the pianoforte was made after the 1885 exhibition. It has been suggested that some pianos were placed in lesser local exhibitions, to give them a greater chance of obtaining a medal. Here are some of the medals awarded for pianos at early Paris Expositions, before London got in on the act…

1798 The first Paris Exposition. L'Exposition publique des produits de l'industrie française.

1806 Paris Exposition included pianos by Dupoirier, Pfeiffer and Schmidt.

1819 Erard frères Gold Medal.

Pfeiffer, Paris Silver Medal.

1823 Erard frères & Jean Henri Pape received Gold Medals.

Petzold, Pfeiffer & Roller received Silver Medals.

1827 Erard & Pleyel received Gold Medals.

Beckers & Bernhardt received Bronze Medals.

1834 Paris Exposition: Pleyel received a Gold Medal.

Kriegelstein & Plantade received a silver medal.

1836 Paris Exposition: Cluesman, Paris received a Gold medal.

1839 Paris Exposition: Pleyel received a Gold Medal.

Kriegelstein & Plantade received a silver medal.

Pape showed his Piano Console, patented in 1837.

Console Pianos which mention the exhibition were made after the event.

1844 Paris Exposition: Pleyel received a Gold Medal.

De Rohden received a Silver Medal for pianoforte actions.

Herce received an award.

1849 Paris Exposition: Pleyel received the Hors de Concours.

Mussard Freres received a bronze medal.

Van Overbergh received a medal.

THE GREAT EXHIBITION

1851 Medal from the Exhibition Of The Works Of Industry Of All Nations, London, appears courtesy of Mary Thrower, and I scanned the medal itself. The original object was much bigger than the picture you see. This event was so much larger and grander than previous exhibitions, it soon became known as the GREAT exhibition, and was held at the purpose-built Crystal Palace. Erards confusingly claimed that theirs was “the only council medal for pianofortes”, but there were several others.

Some of the pianos shown in catalogues of the Great Exhibition.

![]()

1853 New York built its own Crystal Palace, and even imitated the name for their

“Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations”.

1855 Erards received “the highest award” at the 1855 Paris Exposition.

Van Overbergh received “the Grande Medaille”.

Rudd’s pianos received a gold medal.

Gaveau received a Bronze medal.

Herce received a medal.

Having received medals in 1851 and 1855, Erards produced commemorative discs which resemble small medals, but are easily spotted because they have both dates on them. Although desirable, these are not especially rare or valuable, they are thought to have been distributed to Erard dealers around the world, and stuck onto some Erard pianos.

1857 Rororf & Cie, Zurich, received a silver medal at Bernes.

1862 LONDON EXHIBITION

Pleyel and Hopkinson received medals, but we have no evidence so far that Erard was even there. Foster later claimed a medal as well, but so far, we have no evidence of the existence of a real maker of that name in London during the 1800s, and certainly no sign of him being there in 1862. Arthur Rosenstiel (London) also claimed a medal from 1862, but he was not listed as an exhibitor, indeed I can find no reference to the name in our many London lists of makers between 1862 and 1907, when the name was being used. William Crick’s pianos depicted a medal from the 1862 exhibition, but he is another one not listed in the catalogue as even being there, much less winning a medal. He also claimed Royal Letters Patent, but we have so far been able to find a central source for these, and no evidence has been found to support his claim.

Schiedmayer & Soehne received a medal at the Great Exhibition, 1851.

By 1890, they were boasting 19 first prize medals…

1865 Anglo-French Exhibition, Australia. Henry Brinsmead received a Gold Medal.

1867 Paris Exposition: It seems that no English pianos received medals.

Erard received a medal.

Gaveau received a Silver Medal.

Alois Kern received a Silver Medal.

Jules Rinaldi received an Honourable mention.

Chickering’s literature implies that the Cross of the Legion D’Honneur was the highest award given to a piano manufacturer at the 1867 exposition, superior to the Gold Medal, but in reality, the Cross was awarded to people, not pianofortes.

Medals awarded to Alois Kern, Vienna, in 1867, 1870 and 1873.

Medals from the Chile Exhibitions of 1873 and 1875 show these images of the goddess Minerva, easy to recognise if you can’t read the wording, so they would place a piano after the 1873 exhibition.

1878 Paris Exposition. Gaveau received a Gold Medal.

Monington & Weston received a Gold Medal.

Hopkinson received a Gold Medal.

Charles Gehrling received a Silver Medal for Pianoforte Actions.

1879 Berlin Exhibition: "Dem Verdiensje Seine Krone" is a phrase to which references can be found from at least 1849 to 1903, the latter the title of a literary work: It means "The merits of his crown" but should perhaps translate more like "To the service of his crown", probably a bit like "By Royal appointment". The same phrase appears on exhibition medals awarded to Bergstein, Dietzer, Haller, Laurinat, Lubitz, Reisner, Schiemann, Schotz, Steinbeg & Weber, and these are mostly from the Berlin exhibition of 1879.

1880 Melbourne exhibition. Fritz Kuhla’s pianos claimed some sort of medal, but Erard, Herz, Bord, Debain and Gehrling all received gold medals.

1881 Melbourne Exhibition. Can anyone tell me about a firm called Rose that received a gold medal there?

1884-85 H. Kohl received a medal at “Queen Victoria’s Jubilee Exhibition”,

which is odd because her Jubilee was not until 1887!

1885 INTERNATIONAL INVENTIONS EXHIBITION

1885 Schwander received a medal for his piano actions.

Cresswell Ball claimed a medal, but our Cresswell Ball piano was made by the McVay Pianoforte Co..

1885 Arthur Allison's medal is attributed to the International Inventions & Music Exhibition 1885.

This was possibly the same Inventions Exhibition at which Steinways won 2 gold medals.

1885 J.D. Cuthbertson, Glasgow piano is also marked “G Klingmann & Co. Berlin”.

It has small gold discs which read “Gold Medal Alexandra Palace and International Exhibition 1885”.

1885 Hopkinson received the Gold Medal at the London Inventions Exhibition.

Chappell, Ajello & Allison also received prize medals.

1885 Robert Grout received an exhibition award for his pianos.

1885 Gold Medal awarded to G. Ajello at the International Inventions Exhibition.

1885 Squire & Longson Exhibition medal.

1885 Niedermayer received a medal at the International Inventions Exhibition.

1887 A small ad in the Music Trades Review mentions Schiedmayer's 1885 medal,

describing it as THE gold medal, in spite of all the others.

1887 Another International Inventions Exhibition was held in Sweden.

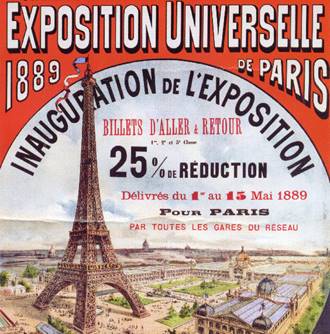

1889 PARIS EXPOSITION

Focke, Paris, received a Gold Medal.

Michelle Wenham wrote to me about the piano above, made by A.H.Francke, Leipzig, some time after his 1876 patent. It is believed to have been bought from a Paris Exposition, possibly the 1889 one, but the publications about that event are so obsessed with the Eiffel Tower, they say very little about the pianos, and although we know Steinway was there, no reference to Francke has been found yet. Some people would say the piano looks like Art Nouveau, but it seems a bit early. It has the convex shape to the top, which is most commonly found around the 1870s. A faded label suggests that Francke had received 8 exhibition medals, and we know that by 1882, he had about 13, mainly from Germany and Vienna, so it may be that the piano was made between 1876 and 1882, and the 1878 Paris Exposition seems a possibility. The righthand photo is one that I took, looking up under the Eiffel Tower, and showing the green nets used to catch anyone who tries to jump off. What is surprising is that a piano maker like Francke received all those medals, yet very little information is available about him or his pianos. He died in 1882, but the firm continued, and there was still one of the same name in Berlin, 1928.

This transfer shows that Fritz Kuhla’s pianos received medals at the Melbourne Exhibition, 1880,

and the Berlin Exhibition, 1896.

Victorian Hopkinson pianos were “Awarded the First Class Prize Medals 1851, 1855, 1862, 1865 & 1872”.

Single sides of 8 different medals awarded to Hopkinson up to 1910 are shown here. Among those, Hopkinson claimed to have received “the only Gold Medal for Great Britain” at the 1878 Paris Exposition, but Monington & Weston’s centenary leaflet proudly shows a picture of their upright which won "The" Gold Medal at the 1878 Paris Exposition! Barratt & Robinson received an honourable mention. It is odd that some of Hopkinsons’ pianos make no mention at all of the medals.

Without donations, I will be fine, but our collection may not survive for future generations, and it may all end up on a bonfire. People plead with us to save their pianos from destruction, but it is often difficult to justify the transport costs. If every visitor to this site made a small donation, we would have better displays for our building, and much-improved facilities for research within our own archives. Cheques must be made out to Bill Kibby-Johnson. Foreign cheques are subject to high bank charges, so if you are posting a donation, bills are easier to change without any of your money disappearing on charges.

1887 Several jubilee exhibitions around Britain celebrated the 50th year of Queen Victoria's reign.

1888 The Anglo-Danish Exhibition was opened by Their Royal Highnesses the Prince and Princess of Wales.

Avill & Smart received an award for their pianos.

Spencer’s medals from Melbourne, 1888 and Edinburgh, 1890,

and a reference to his Royal Appointment to the Princess of Wales.

1889 Gaveau received a Gold Medal at the Paris Exposition.

Schwechten’s medals up to 1891.

Henry Hicks seems to have received 2 gold medals in London, in 1870 and 1899, but his name transfer and stationery do not give any real clues to the source of these, so they were probably minor local exhibitions.

Pleyel’s medals up to 1887, from our 1892 Post Office London Directory.

If a maker's other medals are listed in our files, then it may be possible to get some better estimate of the age of a pianoforte by finding out which medals are missing, because we have a tremendous amount of information about pianos in exhibitions.

This list of Bluthner’s medals up to 1889 provides a means of checking the approximate date of a pre-1889 Bluthner piano, by seeing which medals are not shown. Here is a more complete list.

1865 1st prize, Merseburg.

1867 1st prize, Paris.

1867 1st prize, Chemnitz.

1870 1st prize, Cassel.

1873 1st prize, Vienna.

1876 1st prize, Philadelphia.

1878 1st prize, Puebla.

1880 1st prize, (flugel) Sydney.

1880 1st prize, (pianino) Sydney.

1881 1st prize, (flugel) Melbourne.

1881 1st prize, (pianino) Melbourne.

1883 1st prize, (flugel) Amsterdam.

1883 1st prize, (pianino) Amsterdam.

1889 1st prize, (flugel) Melbourne.

1889 1st prize, (pianino) Melbourne.

1894 Hors concours, Antwerp.

1897 Grand prize, Guatemala.

1897 Leipzig Auss.Preisbewerb.

1900 Paris Grand Prix.

1904 St. Louis Grand Prix.

1905 1st prize, Cape Town.

1910 Grand Prix, Brussels.

If, for example, the label doesn’t show any medals after 1876, you can reasonably suppose that it was made after the 1876 exhibition, but before the 1878 exhibition. In reality, Bluthners are probably the least reliable example of this idea, because on occasions when they reconditioned their own pianos, they were one of the few makers that sometimes updated the list of medals.

The so-called "Columbian Exposition" (nothing to do with Columbia or Colombia) took place in Chicago, 1893, to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the landing of Christopher Columbus, although he would have had a hard job landing in Chicago, and it seems to have been a tenuous excuse to promote the city. Dvorak wrote his wonderful New World Symphony for the event, with so many memorable themes. Newman Brothers showed organs. Bent, Bush & Gertz, Cable, Everett, Felumb, Kimball, Kingsbury, Lehr, Melville Clark, Orpheus, Reed & Sons, Starck, Starr, Strauch and Vose showed pianos, and almost all of them received medals, which seems to devalue the whole process. Everett, Starr and Strauch Bros all claimed "The Highest Award" at the Columbian Exposition, but Kimball, who received a medal, said they were "The only manufacturer thus honored". Reed & Sons' piano was awarded a grand prize medal and other distinctions at the Columbian Exposition. People reading information written on instruments naturally assume that the individual piano was actually there at the exhibition, or even won a prize medal, whereas this is usually general information written on hundreds or thousands of pianos made in the years after the exhibition, some certainly as late as 1914. All we can say is that the piano was made after 1892. One of the exhibitors was Emil Felumb, Copenhagen…

Emil Felumb’s medals from 1881 to 1896. The undated one on the left is from Paris, possibly 1878.

Both sides of J.L. Duysen’s 4 medals up to 1892.

Henri Herz’s medals and awards.

Around 1901-2, Osbert pianos show undated illustrations of 6 sides of exhibition medals, and it would be easy to assume that they are both sides of 3 medals, but they mention Vienna, London, Paris, Bruxelles and Berlin, so 5 events. The additional puzzle is that we can find no evidence that Osbert Ltd. ever had a piano factory.

Our T.G. Payne piano shows both sides of a single medal from the Glasgow Exhibition, 1904.

Georg Hoffmann, Berlin medals for 1902 and 1903, plus an anonymous single side.

Strohmenger’s medals up to 1905.

John Brinsmead was awarded an incredible number of medals. Here, for example, are the ones up to 1907…

1851 London

1862 London

1867 Paris

1869 Netherlands

1870 Paris Gold Medal

1874 Paris

1876 Philadelphia

1877 South Africa

1878 Paris

1880 Queensland

1881 Melbourne

1882 New Zealand

1883 Rome

1883 Portugal

1883 Cork

1883 Amsterdam

1884 Bavaria

1884 Calcutta

1884 London

1885 Antwerp

1885 Cape Town

1886 Ctania

1886 Naples

1886 Western Australia

1888 Barcelona

1889 Algiers

1890 Edinburgh

1891 Jamaica

1895 Tasmania

1897 Brisbane

1898 Dunedin N.Z.

1899 Auckland N.Z.

1902 Wolverhampton

1906 Cape Town

1907 Christchurch N.Z.

1907 Dublin

Almost anyone who sells second-hand postcards will have some from the Franco-British Exhibition of 1908, there is part of one at the top of this page, and their output of cards was enormous at a time when picture postcards were a fairly new idea, but we have found no catalogues or details of the various pianofortes that claimed medals there, including Boyd, Diener, Gresham, Mozart, Rudall Carte, Thalberg, and Vader.

28 medals and prizes awarded to Gaveau, Paris, up to 1913.

Berdux, Munich, received these 9 medals up to 1911.

1946 “Britain can make it” Exhibition.

Imagine, you are offering a piano for display, to represent the best that Britain can make, and Monington & Weston exhibited this bog-standard grand mounted on the kind of unfinished legs that were used on coffee tables, but bigger.

Monington & Weston’s stand at the 1951 British Industries Fair.

I worked on similar stands at the Ideal Home Exhibition for Berry Pianos in the sixties.

Pianogen.org paino panio pisno ponia piano history collection Bill Kibby

ACTIONS – ALIASES - ANCESTORS - ARCHIVES - AWARDS - BLOG –

DATEMARKS – DEMOS – DIAGRAMS – DONATIONS – DRY HEAT DAMAGE –

EDWARDIAN - EXHIBITION – FALSENESS - GENEALOGY – GEORGIAN – GRAND –

HEALTH – INVENTOR - KEYS – MEDALS - MEMORIES - NAMES – NUMBERS –

OCTAVES - QUERPIANOS - REPERTOIRE – SQUARES – STENCILS – TUNING –